This webpage is dedicated to the Maestro PS-1 Phase Shifter manufactured during the 1970's.

In 1971 a new effects device hit the musical instrument market and made an immediate impact on the sound of the electric guitar. That device was the now-legendary Maestro PS-1 Phase Shifter. Within weeks of its release, the sound of phase shifted guitars and keyboards began resonating over American radio airwaves and the phase shifter craze was on. Almost immediately, other manufacturers followed suit and began offering phasers of their own design in an effort to cash in on the new phase shifter fad. However, the Maestro Phase Shifter was and still is the original. The PS-1 ruled as king of the phasers for quite some time, and although it was eventually replaced by units that were smaller and less expensive, the Maestro PS-1 remains unique in many ways. In fact, the Maestro Phase Shifter has never really been equaled. Even today, it continues to be championed by loyal enthusiasts, and some thirty years after its release, the sound of the Maestro Phase Shifter can still be heard whirling and swirling on new recordings.

So - just what makes the Maestro Phase Shifter so special? Why do guitarists scour the web and wade through the backrooms of music stores in search of this ancient mystical beast? And - if it WAS such a good phaser, why did Maestro stop offering it in the first place? For that matter, who WAS Maestro?

Who was Maestro?

Maestro was the name used by Gibson to market its innovative line of guitar effects boxes during the 1970's. But this was not the first time that the Maestro name had been used by Gibson. In fact, the Maestro name goes quite a ways back and has a long convoluted history itself. Let's jump into the Way Back Machine and venture back in time a few years.

Chicago Musical Instruments

Chicago Musical Instruments (CMI) was an enormous musical instrument marketing empire created by a man named M.H. Berlin. Berlin got his start at Wurlitzer's music store in Chicago. In 1919 he opened the Martin Band Instrument Company, renaming it the Chicago Musical Instrument Company six months later. CMI quickly became a full-line distributor of musical instruments; then, Berlin began to search out opportunities to manufacture instruments. By 1941, the CMI empire included Olds (trombones), Penzel Mueller (clarinets), Scandalli and Dallape (accordions), National (guitars), and Symmetricut (reeds). In 1944 CMI acquired the Gibson Guitar Company and a period of dramatic growth began for that company. CMI distributed a line of accordions under the Maestro name in the early 1950's and in 1955 Gibson began to offer a line of amplifiers for accordions under the Maestro name. Gibson stopped production of those amplifiers in 1961, but the Maestro name resurfaced on a Gibson vibrola tailpiece.

Maestro as an Electronics Division

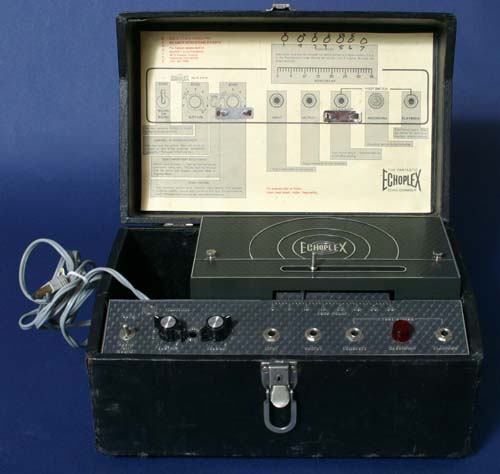

In 1959 CMI began selling the Echoplex tape echo built by Market Electronics of Cleveland, Ohio under the Maestro name. The Echoplex enabled musicians to duplicate the echo sounds they obtained in the studio with echo chambers, and the Echoplex offered some sounds of its own that became studio recording staples.

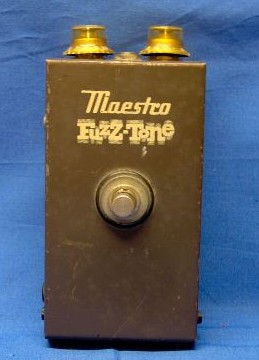

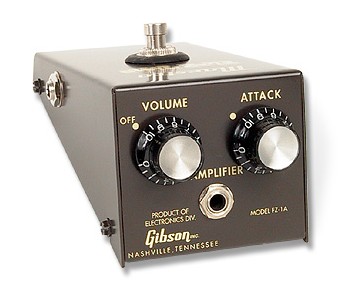

By the early 1960's electric guitars were all the rage and Gibson expanded rapidly to meet the demand. In 1962 Gibson amplifier production was moved away from the main plant and into its own facility in an effort to accommodate the rising demand. Two years later amplifier manufacturing had to be moved once again into a larger building. Electric guitars and amplifiers led to further advances in electronics. Gibson introduced the world's first commercially available fuzz-tone effects box in 1962 and dubbed it the Gibson Maestro FZ-1 Fuzz-Tone. The design evolved into the FZ-1A in 1964. Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones used a Maesto Fuzz-Tone on the recording of Satisfaction and Maestro Fuzz-Tone sales went through the roof.

The Maestro product line quickly expanded and included the Boomerang Wah/Volume pedal, Full Range Booster, Envelope Modifier, Octave Box, Sustainer, Bass Brassmaster, Sireko, and many others. The company introduced a very popular line of analog rhythm machines. Maestro evolved into a full fledged musical effects and electronics division within the CMI empire. Interestingly, many of Maestro's products were actually designed and manufactured by outside contractors. Several of Maestro's effects boxes such as the Bass Brassmaster and the Octave Box were bizarre sounding. Maestro ads often showed pictures of their product line on the surface of the moon - apparently the company was well aware of the radical reputation of its products and were quite proud of it!

Enter Tom Oberheim

Around 1968 a UCLA physics graduate named Tom Oberheim designed an effects box called a Ring Modulator. A ring modulator mixes the source sound with the output of an internal oscillator to produce sum and difference signals that are mathematically, but not necessarily musically, related; in short it creates weird dissonant sci-fi sounds. Tom built a few of the units for friends and local musicians. One of the units found its way into the hands of movie composer Leonard Rosenmann. Rosenmann wanted to use Obereheim's Ring Modulator on the movie score for Beneath the Planet of the Apes so he called Tom and asked him to bring one of the units down to the studio. Oberheim showed up at the 20th Century Fox Studio with the ring modulator and demonstrated it, putting his radical device through its paces. Three of the orchestra musicians were so impressed that they ordered units right on the spot. In 1970 Tom got a call from CMI, who wanted to add the ring modulator to their product line. Oberheim suddenly found himself in business as a manufacturing contractor for Maestro.

Around this time Tom was hanging out with members of a band called Bryndle (Karla Bonoff, Wendy Waldman, Andrew Gold, and Kenny Edwards) who, like many other musicians of their day, frequently ran their instruments through Leslie rotating speaker cabinets. Tom was intrigued by the sound of the Leslie and set to design an effects box that could mimic the sound of the rotating speaker cabinet. The result was the PS-1 Phase Shifter. In 1971 Tom talked Maestro into marketing it. Although Maestro agreed to sell the unit they were somewhat skeptical about its success because its sound was far less radical than the Fuzz-Tones and Ring Modulators they were selling. The effect of the PS-1 Phase Shifter was fairly subtle - at least when compared to a Fuzz-Tone or Ring Modulator. But the warmth and subtlety of the PS-1 was its strength. It was possible to use phase shifting on just about any guitar or keyboard part without going too far over the top. Over the next four years Maestro would sell 60,000 of the units.

Oberheim went on to design other effects for Maestro, including a big monster called the Maestro Universal Synthesizer, which really wasn't a synthesizer at all but rather a complex multi-effects unit that included a phaser, a filter/sample hold effect, a distortion, an envelope follower, and an octave divider.

The Design of the PS-1

The Maestro Phase Shifter was not intended for floor operation; rather, it was designed as a table-top type of unit. The chassis is made from bent sheet metal. The top of the unit is slightly angled for improved visibility of the control panel. A rather thick plate is welded to the bottom of the unit and is threaded for a standard microphone stand; in this manner, the unit can be attached to a mic stand and conveniently placed near the guitarist on stage for easy access to the controls. A six-pin Molex type connector located on the rear of the unit provides connection to an optional three-button footswitch that duplicates the operation of the three buttons, providing remote foot control of the phaser.

Three colorful buttons located on the top of the unit select the phasing speed. The buttons are appropriately labeled SLOW PHASE, MEDIUM PHASE, and FAST PHASE. The SLOW PHASE button also functions as the bypass switch. Interestingly, the three colorful plastic buttons were the same as those used on Lowery organs. CMI also owned Lowery at the time and suggested the use of the colorful Lowery buttons for speed selection. One unique and very cool aspect of the Maestro Phase Shifter is the fact that the phasing speed ramps up or down when changing from one speed to another, similar to a Leslie rotating speaker cabinet. This feature is not to be overlooked or underemphasized!!! The dynamic effect produced by the ramp-up/down feature sounds absolutely superb when used by an accomplished musician - no other phaser offers this feature and that alone makes the Maestro Phase Shifter worth the price of admission!

The Maestro Phase Shifter is AC powered and uses a non-polarized AC cord. A switch on the top of the unit turns it on and off. A fuse is provided on the rear of the unit. The classic Maestro emblem with its three colored "trumpets" is proudly displayed on the top of the unit.

The PS-1 is a six-stage phase shifter. It utilizes Field Effect Transistors (FETs) as tuning elements for six cascaded all-pass filter networks with the input and output summed. An LFO modulates the FET control buss and includes a time constant so that when the LFO speed changes, it ramps up or down slowly, simulating the speed change of a Leslie speaker cabinet.

PS-1 Versions

Initially, the Maestro Phase Shifter was released as the PS-1. Shortly after its release, it evolved into the PS-1A. Later an additional Variable Speed control knob was added on the top of the chassis and the unit became the PS-1B. This was the final version of the PS-1 Phase Shifter. There were far more PS-1A versions produced than either the PS-1 or PS-1B versions.

Sonic Character or Defect of Character?

In addition to its magnificent phasing effect, the Maestro PS-1 Phase Shifter had one other very noticeable sonic characteristic - or defect - depending on your point of view. Like most other effects of its time, the Maestro did not include True Bypass Switching. A Maestro Phase Shifter placed in the signal path between a guitar and amplifier creates a noticeable reduction in high-end brilliance while adding overall strength to the mid range. Even with the phasing turned off, the sound of the guitar passing through the Maestro is fatter but with less high-end detail. Some people like this effect and say that the Maestro "warms up" their guitar; others say that it reduces the brilliance and clarity of their guitar. It's one of those things where you either like it or you don't. The phenomenon was not unique to the Maestro Phase Shifter - but it's pretty noticeable. Back in the 70's I was using a PS-1A with Marshall (non-master volume) tops and the reduction in high end really bothered me; as a result I eventually sold my PS-1. A couple of years ago I started modifying and building effects pedals and learned a lot in the process. Recently I bought another PS-1 and modified it with True Bypass Switching; this totally alleviates the high-cut problem. If you want to know more about this, see the Maestro PS-1 Technical Notes page.

Meet the New Boss (Not the Same as the Old Boss)

In December of 1969, Chicago Musical Instruments, the parent company of Gibson and Maestro, merged with (business speak for "was taken over by") an Ecuadorian company called ECL. ECL owned numerous companies including several South American beer breweries. They had no previous experience with the manufacturing of musical instruments whatsoever. In 1970, the new corporation was renamed Norlin (after the company's chief officers Norton Stevens and M.H. Berlin). Ultimately, Berlin would be squeezed out of the company. Whereas Berlin had been a man with vision it would soon become obvious that the new owners of Maestro were nearly blind. However, that was still a few years away - in 1970 expectations of success were high and the mood at Norlin was very upbeat and confident - Norlin was on the fast track and in high gear.

Phase shifting was extremely popular and Maestro decided to expand their phaser product line. The PS-1 was a big seller, but it was expensive and was out of reach for many musicians, so Maestro introduced the MPS-2 Mini-Phase, also designed and built by Oberheim. The Mini-Phase was smaller and less expensive. It sat alongside the original PS-1 in the Maestro catalog for a while, with the PS-1 being the "Cadillac" phaser model and the Mini-Phase the "economy" model. But both units were doomed to short lives as changes in the corporate world lay just around the corner.

Enter Moog, Exit Oberheim

In 1973 Norlin acquired Moog, a major builder of synthesizers and effects processors. It probably seemed logical at the time to have Moog build Maestro's effects rather than use an outside contractor like Oberheim. At any rate, in January of 1975 Norlin suddenly cancelled all orders with Oberheim and put Moog in charge of developing the Maestro effects line. Moog quickly revamped the entire line and the PS-1 was "phased out". Maestro sold off the existing Oberheim-built stock and phased in the new Moog-built products. Tom Oberheim attempted to market effects under his own name for a while, but when that effort proved unsuccessful, he moved onto another more promising venture. Oberheim moved into the new lucrative world of synthesizers and did very well. Oberheim synths are the stuff legends (and platinum records) are made of, but of course, that's another story.

While there was really nothing wrong with the design of the "Moog era" Maestro effects boxes, the overall ambience of the Maestro product line changed dramatically. However, like the Oberheim-built effects that preceded them, the life expectancy of the Moog-built Maestro lineup was about to be cut short too as still more market and corporate changes approached.

The Fall of Rome

By the time Norlin handed over the development of Maestro effects to its new Moog division, the Norlin corporation was already in a state of turmoil. Norlin, barely five years old at the time, was already showing signs of a corporation entering a tailspin. When Norlin acquired CMI they had immediately filled the management ranks with MBAs who had no previous experience with musical instrument design and manufacture. They had also built an enormous bureaucratic management structure with little sense of direction. There are stories about Norlin management making a decision in the morning only to completely reverse themselves by that afternoon. One Gibson manager has said that corporate decisions were changing so quickly that it was becoming impossible for anyone to keep up. Norlin began spending money twice as fast as it earned it. Then, when the American economy (and hence the musical instrument market) entered a slowdown in the late 70's, Norlin found itself overextended and in a serious financial situation.

Exit Maestro, Exit Norlin

Moog had developed an innovative (although much smaller) line of effects for Maestro, but they too would be short-lived as nobody would be able to save Norlin from its inevitable collapse. Norlin began selling off its companies one by one in an effort to stay afloat, eventually divesting itself of all its musical instrument divisions. Norlin stopped production of Maestro effects in 1979. Norlin sold off Moog in 1983. Lowery was sold in 1985. Gibson was sold in January of 1986. Every Norlin division was impacted - they even sold off the brewery business that had been the original source of all their now rapidly disappearing wealth. Incredibly, in the middle of all this financial turmoil, Norlin managed to take out a bank note in 1983 for 55 million dollars and purchased Ticor Print Network, Inc. When the print business went bust in 1993 what was left of Norlin merged with Pitney-Bowes.

Rising From the Ashes

In January of 1986, Gibson was purchased by an investment group that included Henry Juszkiewicz, David Berryman, and Gary Zebrowski. Juszkiewicz, Berryman, and Zebrowski had previously purchased Phi Technologies, a troubled Oklahoma City high-tech firm and had turned that company around. They set out to do the same with Gibson. Ultimately, the new Gibson team would rebuild Gibson into a first class guitar manufacturing company. Gibson acquired Steinberger (guitars) in 1987, Flatiron (mandolins) in 1987, and Tobias (basses) in 1989. Eventually, the new owners of Gibson would go to acquire other companies and began to reassemble much of the former CMI empire. The Gibson empire now includes Epiphone (guitars), Baldwin (pianos), Wurlitzer (keyboards), Slingerland (drums), Dobro (resonator guitars), Orange (amplifiers), and - hold your breath - Oberheim!

Today and the Road Ahead

In an ironic twist of fate, the present day Gibson company re-acquired the rights to the Maestro name and reissued the Maestro FZ-1A Fuzz-Tone effect in 2001. The reissue FZ-1A has met with considerable success. One can only hope that Gibson will eventually see fit to reissue the Maestro PS-1 Phase Shifter as well.

Time sorts out the meaning and importance of events. What may appear at the time as seemingly random or disconnected events may converge in unexpected ways. Over thirty years ago an accordion amplifier built by a guitar company, a movie called Beneath the Planet of the Apes, a band with a singer named Karla Bonoff, two brilliant synth engineers named Oberheim and Moog, an organ company named Lowery, and a few Ecuadorian beer breweries all had a part in the story of a truly unique and innovative guitar effect.

In the meantime, buy an old Maestro PS-1, crank up your guitar amp, and set your phaser to stun!

Maestro PS-1 Technical Notes

Wingspread Records Homepage

Copyright © 2026 Wingspread Recording Ltd. Co.